JPEG: The Format That Won't Die

Everything you need to know about JPEG - the 30-year-old image format that still dominates the web. History, how it works, quality settings, and when to use it.

Table of Contents

- What is JPEG?

- Why JPEG won

- How JPEG compression actually works

- Quality settings: What the numbers actually mean

- See the difference yourself

- Common JPEG settings explained

- Chroma subsampling (4:4:4, 4:2:2, 4:2:0)

- Progressive vs Baseline

- When to use JPEG

- ✅ Perfect for:

- ❌ Not good for:

- JPEG optimization tips

- Start with quality originals

- Don’t re-save JPEGs repeatedly

- Use the right quality for the use case

- Strip metadata

- Consider modern formats for new projects

- Common JPEG problems and solutions

- Problem: Banding in gradients

- Problem: Blocky artifacts

- Problem: Blurry text

- Problem: Colors look different across devices

- Problem: File size is huge

- JPEG variants you might encounter

- JPEG 2000 (.jp2, .jpf, .jpx)

- JPEG XR (.jxr, .wdp)

- Progressive JPEG

- Converting to and from JPEG

- From RAW files

- From PNG

- From JPEG to other formats

- The future of JPEG

- Quick reference: JPEG quality guide

- Command-line tools

- ImageMagick

- mozjpeg (better compression)

- Using our tool

- The bottom line

JPEG has been around since 1992. That’s over 30 years. In tech years, that’s basically prehistoric. Yet it’s still the most widely used image format on the internet. There’s a reason for that.

JPEG remains the most widely-used image format on the web, 30+ years after its creation

What is JPEG?

JPEG stands for Joint Photographic Experts Group - the committee that created it. Most people just say “JPEG” or “JPG” (they’re the same thing; the three-letter extension is a holdover from old Windows file systems).

It’s a lossy compression format, which means it throws away some image data to make files smaller. The trick is throwing away the right data - stuff your eyes won’t really notice is missing.

Key features:

- Lossy compression (smaller files, some quality loss)

- 24-bit color (16.7 million colors)

- No transparency support

- Progressive loading option

- Universal support (literally every device and browser)

Why JPEG won

Back in the early 90s, bandwidth was expensive and hard drives were tiny. A single uncompressed photo could be 10+ MB. JPEG could compress that down to 200 KB while still looking pretty good.

That was revolutionary. Suddenly you could actually share photos over the internet without waiting 20 minutes for them to download over dial-up.

But the real genius? The compression algorithm was smart enough to preserve what matters:

- Smooth color transitions (like skin tones)

- Overall shapes and structure

- The “feeling” of the image

What it sacrifices:

- Fine details (sharp edges can get a bit fuzzy)

- Text (gets blurry and weird-looking)

- Repeated patterns (compression artifacts show up)

For photographs, this trade-off works brilliantly. For graphics, logos, or screenshots with text? Not so much.

How JPEG compression actually works

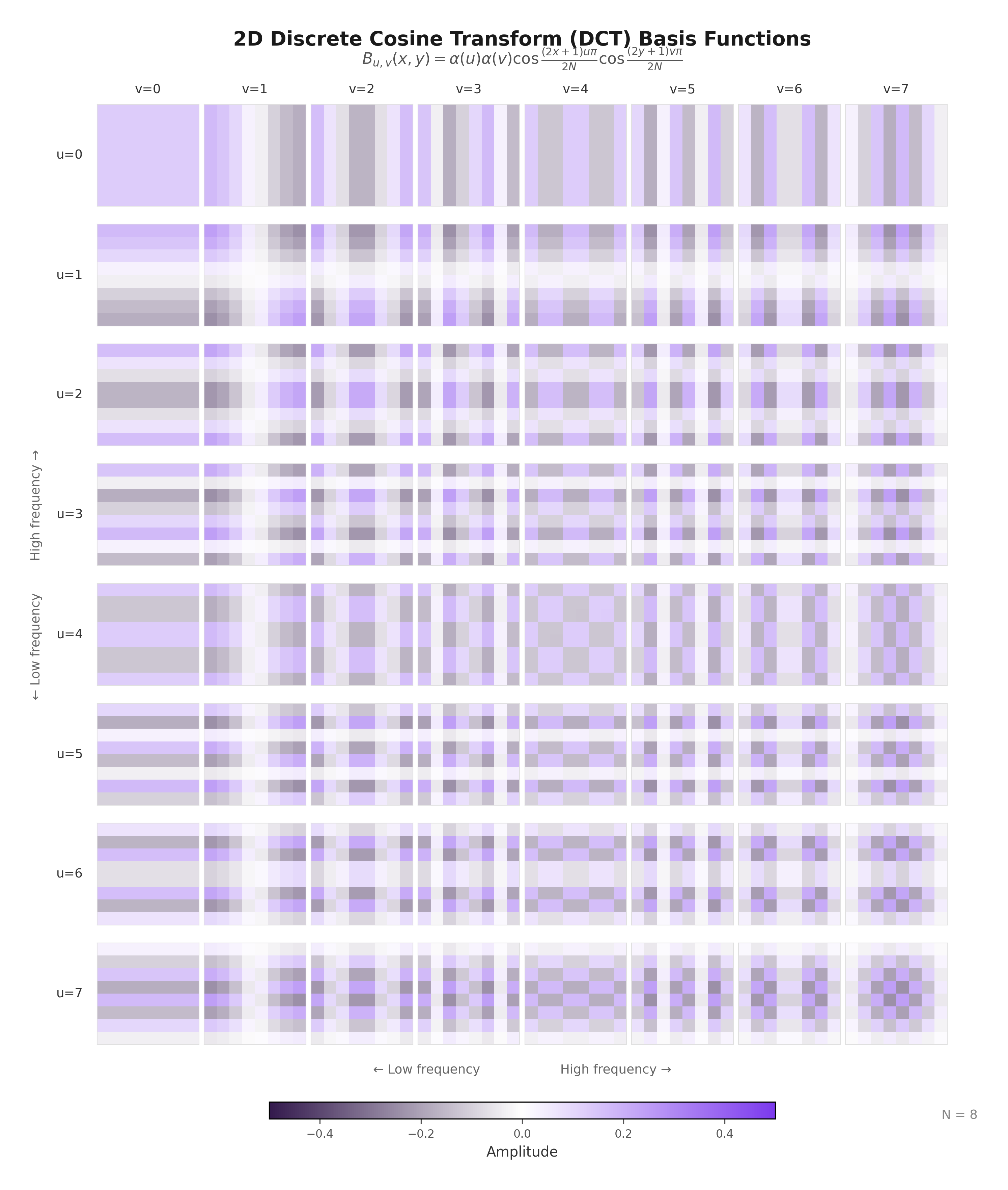

Without getting too deep into the math (there’s a lot of discrete cosine transforms involved), here’s the basic idea:

The four stages of JPEG compression: chroma subsampling, block division, quantization, and encoding

1. Chroma subsampling Your eyes are way better at seeing brightness differences than color differences. JPEG exploits this by storing full detail for brightness but lower resolution for color information. You don’t notice, but the file gets smaller.

2. Block-based compression JPEG splits your image into 8x8 pixel blocks and compresses each one. This is why you sometimes see blocky artifacts in low-quality JPEGs - you’re literally seeing those 8x8 blocks.

JPEG divides images into 8×8 pixel blocks - visible in low-quality images as blocky artifacts

3. Quantization This is where the actual data loss happens. The algorithm rounds off numbers based on what your eyes are likely to notice. Higher quality = less aggressive rounding. Lower quality = more aggressive rounding = smaller files.

4. Huffman encoding Finally, it uses lossless compression (like a ZIP file) to squeeze out a bit more space without losing any additional data.

The whole process is one-way. Once you save a JPEG, you can’t get back what was thrown away. This is why you should always keep your originals.

Quality settings: What the numbers actually mean

When you save a JPEG, you usually pick a quality from 0-100. But what does that actually mean?

Quality 90-100 (Maximum quality)

- File size: Large (sometimes larger than PNG)

- Visual quality: Basically indistinguishable from original

- Use case: When you need the absolute best quality and file size doesn’t matter

- Reality check: Quality 95+ is usually overkill for web use

Quality 80-90 (High quality)

- File size: Medium

- Visual quality: Excellent, minimal visible artifacts

- Use case: Professional photography, portfolio work, hero images

- This is the sweet spot for most photography

Quality 70-80 (Good quality)

- File size: Small to medium

- Visual quality: Good for most uses

- Use case: General web images, blog photos, product images

- Recommended for most website images

Quality 60-70 (Acceptable quality)

- File size: Small

- Visual quality: Noticeable compression, but usually acceptable

- Use case: Thumbnails, image previews, mobile-optimized images

- Trade-off: Smaller files, faster loading, slightly degraded quality

Quality 50 and below (Low quality)

- File size: Very small

- Visual quality: Obvious artifacts and blockiness

- Use case: Emergency bandwidth saving, ancient website compatibility

- Avoid unless you have a very specific reason

Here’s the thing: the difference between quality 85 and quality 95 is often invisible to the human eye, but the file can be 40-50% larger. Always test with your actual images.

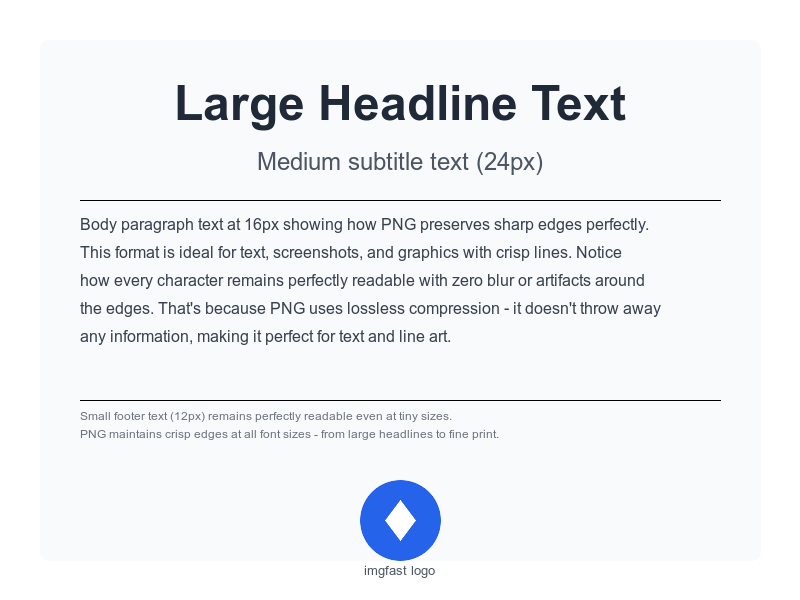

See the difference yourself

JPEG Quality Comparison: 95 vs 85 vs 70

Same photo at different quality settings. Notice how quality 85 looks nearly identical to 95 but is much smaller.

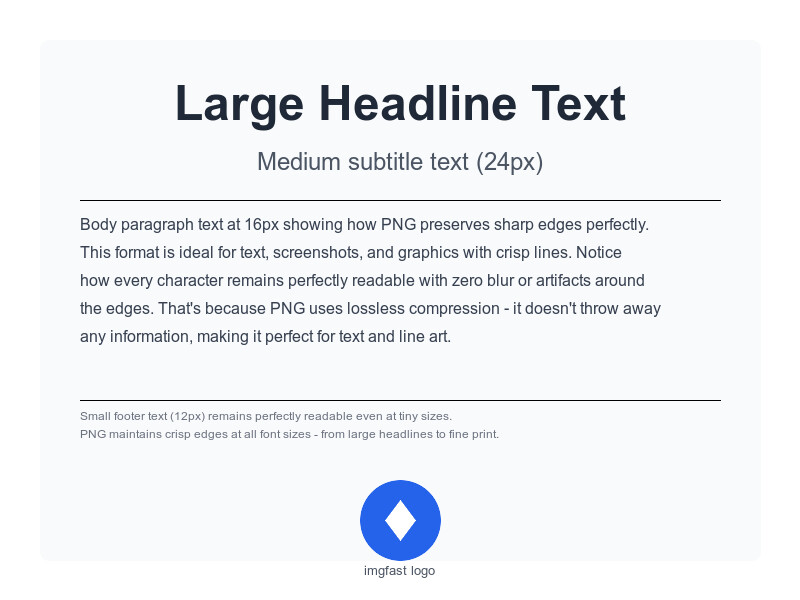

JPEG Quality Problems: Text and Graphics

JPEG struggles with sharp edges and text. See why you shouldn't use JPEG for graphics.

Common JPEG settings explained

Chroma subsampling (4:4:4, 4:2:2, 4:2:0)

These weird numbers control how color information is stored:

4:4:4 - Full color resolution (no subsampling)

- Largest files

- Best quality for images with fine color details

- Rarely worth it for photographs

4:2:2 - Half horizontal color resolution

- Medium file size

- Good balance for most uses

- Hard to spot the difference from 4:4:4

4:2:0 - Quarter color resolution (half horizontal, half vertical)

- Smallest files

- Default for most JPEG encoders

- Works great for photographs

- Your eyes genuinely can’t tell the difference most of the time

Please note, that any chroma subsampling will change the color of the image and effect is more prominent on highly-detailed images. Red has amazing demonstration for that. If you need the most accurate color reproduction - you have to use 4:4:4.

Having said that, for 99% of photos, 4:2:0 is fine. Don’t overthink this one.

Progressive vs Baseline

Two ways a JPEG can load:

Baseline JPEG

- Loads top to bottom like a window blind opening

- Slightly smaller file size

- Better for really small images

Progressive JPEG

- Loads blurry first, then sharpens

- Better user experience (people see something immediately)

- Slightly larger file size (usually 1-5%)

- Better for web use, especially on slow connections

Most modern tools default to progressive. It’s usually the right choice.

When to use JPEG

✅ Perfect for:

Photography - This is what JPEG was designed for. Landscapes, portraits, products, anything with smooth color transitions.

Large images - The bigger the image, the better JPEG’s compression advantage. A 5000x3000 photo might be 15 MB as PNG, but 500 KB as JPEG.

Complex scenes - Lots of colors, gradients, natural textures - JPEG handles these beautifully.

When everyone needs to open it - JPEG works everywhere. Your grandma’s 10-year-old phone can open JPEGs.

❌ Not good for:

Graphics with text - Text gets blurry. Use PNG or SVG instead.

Line art or comics - Sharp edges and solid colors show compression artifacts. PNG is better.

Images you’ll edit repeatedly - Every time you save a JPEG, you lose a bit more quality. Use lossless formats (PNG, TIFF) for working files.

Transparency - JPEG doesn’t support it. Use PNG or WebP.

Small icons or logos - PNG is usually smaller for simple graphics.

JPEG optimization tips

Start with quality originals

Converting from a low-quality JPEG to a high-quality JPEG doesn’t add back the lost information. Garbage in, garbage out. Always start with the best quality source you have.

Don’t re-save JPEGs repeatedly

Each time you save a JPEG, you lose a bit more quality. Do all your editing, then save once at the end. If you need to edit later, go back to the original if possible.

Use the right quality for the use case

- Hero images: Quality 85-90

- Body content images: Quality 75-85

- Thumbnails: Quality 65-75

- Previews/placeholders: Quality 50-60

Strip metadata

JPEG files can contain a ton of metadata (EXIF data from cameras, GPS coordinates, editing history). Strip it out for web use:

- Reduces file size (sometimes by 10-20%)

- Protects privacy (no GPS coordinates, camera info, etc.)

- Faster processing

Consider modern formats for new projects

JPEG is great, but WebP and AVIF can give you 30-50% smaller files at the same quality. Use JPEG as a fallback, but serve modern formats when supported.

Common JPEG problems and solutions

Problem: Banding in gradients

Cause: Not enough color information in smooth transitions (like skies)

Solutions:

- Increase quality setting

- Add a tiny bit of noise to break up the banding

- Switch to a format with better gradient handling (PNG for simple gradients, WebP/AVIF for complex ones)

Problem: Blocky artifacts

Cause: Too aggressive compression, those 8x8 blocks becoming visible

Solutions:

- Increase quality setting

- Use progressive JPEG (hides artifacts better during loading)

- If it’s already saved at low quality, you’re stuck - there’s no way to fix it without going back to the original

Problem: Blurry text

Cause: JPEG’s compression doesn’t handle sharp edges well

Solution:

- Don’t use JPEG for text. Seriously. Use PNG or SVG.

- If you must use JPEG, use quality 90+ and it’ll be less terrible (but still not great)

Problem: Colors look different across devices

Cause: Color profile issues (sRGB vs Adobe RGB vs Display P3)

Solutions:

- Always save as sRGB for web use

- Embed the color profile if you need accurate colors

- Test on multiple devices

Problem: File size is huge

Cause: Too high quality, or image is way bigger than needed

Solutions:

- Reduce quality (try 80 instead of 95)

- Resize the image to actual display size

- Use chroma subsampling 4:2:0

- Strip metadata

JPEG variants you might encounter

JPEG 2000 (.jp2, .jpf, .jpx)

A better JPEG that never caught on. Better compression, no blocking artifacts, supports transparency. But basically no browser support, so it’s mostly used in medical imaging and digital cinema. Not for web use.

JPEG XR (.jxr, .wdp)

Microsoft’s attempt at a better JPEG. Better compression than regular JPEG, supports transparency and HDR. Dead on the web. Edge used to support it, but even Microsoft gave up.

Progressive JPEG

Not a different format, just a different encoding method. Same .jpg extension, just loads differently. Generally better for web.

Converting to and from JPEG

From RAW files

If you’re a photographer shooting RAW:

- Edit in your RAW processor (Lightroom, Capture One, etc.)

- Export as high-quality JPEG (quality 90-95)

- Use that as your master file for web optimization

- Never edit the JPEG directly - always go back to RAW

From PNG

If you have a PNG photo that’s too large:

- Converting to JPEG can reduce size by 60-80%

- Quality 85 usually gives visually identical results

- Test before deleting your PNG original

From JPEG to other formats

To WebP: Usually 25-35% smaller at same quality. Do it.

To AVIF: Usually 40-60% smaller. Definitely do it (with JPEG fallback).

To PNG: Only if you need transparency or lossless quality. File will be much larger.

The future of JPEG

JPEG isn’t going anywhere. It’s too entrenched, too universal, too “good enough” for most uses.

But its dominance is slowly fading:

- WebP is gaining ground (96% browser support)

- AVIF is the new hotness (85% browser support and growing)

- JPEG XL might eventually happen (but don’t hold your breath)

The smart play: Use modern formats (WebP, AVIF) with JPEG as fallback. You get the benefits of newer compression while maintaining universal compatibility.

Quick reference: JPEG quality guide

Use Case Quality Typical File Size

---------------------------------------------------------

Hero images 85-90 200-400 KB

Portfolio/gallery 85-90 150-350 KB

Blog post images 75-85 100-250 KB

Product photos 80-90 150-300 KB

Thumbnails 65-75 20-80 KB

Background images 70-80 100-200 KB

Mobile-optimized 65-75 50-150 KB

Email images 70-80 50-100 KB

Social media 75-85 Varies by platformNote: Sizes are for ~1200px wide images. Your mileage may vary.

Command-line tools

ImageMagick

# Basic conversion with quality control

convert input.png -quality 85 output.jpg

# Strip metadata

convert input.jpg -strip output.jpg

# Resize and optimize

convert input.jpg -resize 1200x -quality 80 -strip output.jpg

# Progressive JPEG

convert input.jpg -interlace Plane -quality 85 output.jpgmozjpeg (better compression)

# mozjpeg gives you smaller files at same quality

cjpeg -quality 85 -optimize input.ppm > output.jpg

# Progressive + optimize

cjpeg -quality 85 -progressive -optimize input.ppm > output.jpgUsing our tool

Or just use imgfast and we handle all the technical stuff for you. Upload, pick your quality, download. Done.

The bottom line

JPEG is 30+ years old and still the most practical format for photographs on the web. It’s not the most efficient anymore (WebP and AVIF beat it), but it’s universal, well-understood, and “good enough” for most uses.

Modern strategy:

- Use JPEG as your baseline/fallback

- Serve WebP to browsers that support it (96% do)

- Serve AVIF to browsers that support it (85% do)

- Quality 75-85 is the sweet spot for most photos

- Always use progressive encoding for web

- Strip metadata before publishing

JPEG isn’t going away anytime soon. Master it, because you’ll be using it for years to come.

Related articles:

- WebP: Google’s Modern Format - 25-35% smaller than JPEG

- AVIF: The Next Generation - 40-60% smaller than JPEG

- PNG: When Transparency Matters - For graphics and logos

- Responsive Images Guide - Serve the right size to each device

Questions? We’re a small team and actually read our emails - reach out if you need help with JPEG optimization.